Upon Arrival: Cataloguing New Acquisitions

Hope everyone had a lovely holiday season! I’m writing this blog post in December 2020 and want to share a bit of cheer and colour, so I’ve picked this unusual pair of boots to write about cataloguing, the next step in the Upon Arrival blog series.

The purpose of cataloguing for museums and libraries is to make items in the collection accessible. That is true for the Bata Shoe Museum as well. Successful cataloguing allows items to be retrieved by data searches and allows for items to be easily located physically. Really, cataloguing makes the collection easy to use. So what is involved?

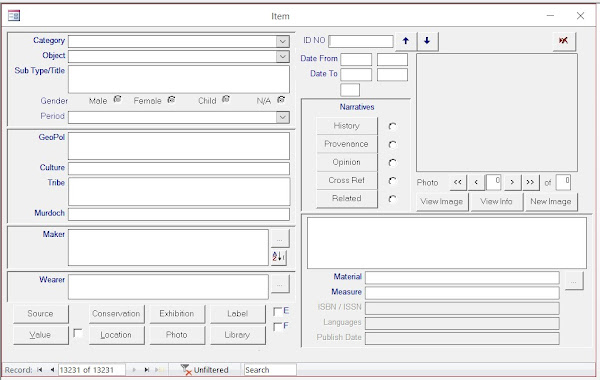

The information system at the Bata Shoe Museum includes paper records as well as this database. The database makes it easy for us to find each item in the collection. Note all of the characteristics that are recorded in the database.Information System

The Bata Shoe Museum holds over 14,000 items. The curatorial team is surprisingly good at remembering many of those items, but to remember all the characteristics of 14,000 items is not humanly possible. To be exact, in the information we pass along to our visitors, we use an Information System, which allows us to enter information on each item distinctly. We add entries to the information system when we catalogue, and once the item is part of the collection, we will add or update the information over time as we learn more about the item through research. The information system is composed of analogue (paper files and logbooks) and digital resources (a database and image server).

Most of the cataloguing is done on the database. Each item takes on average one hour; with some items taking much longer if there is lots of information known about the piece, or interestingly, if lots of time is needed to verify that there is not much information available on the piece.

Cataloguing allows for a close look at the boot to determine its characteristics.To begin, the cataloguer needs to take a good look at the item. The first things to look for are materials and construction. The item could be fragile and those two characteristics are key indicators. On this boot, note the feathers. They are generally fragile and over time will become even more dry and brittle. These boots should not be handled more than absolutely necessary, and a trained handler will know to be very careful with the feathers and also the silk uppers. Once the fragility of the item has been assessed, the full range of materials is noted: silk, metallic silver and gold threads, leather and feathers. The materials are entered in the Material field in order from greatest to least content.

Looking inside the boot, a quilted silk lining and ‘sock’ (or ‘sock lining’, the covering of the insole that the wearer’s foot rests on) are seen. This quilting is insulation to help keep the wearer warm on the carriage or car ride.The construction of the footwear is noted next. Construction is a huge topic on its own that deserves its own blog post, but here let me tell you that for shoes, the term construction relates specifically to how the sole is attached to the upper. There are many methods. This pair of boots are handmade and are constructed with the ‘turn shoe’ method. This indicates that there is a single sole, which during construction, was stitched together while the shoe was inside out on the last. The shoe is then turned right side out and completed. This method achieves a smooth and fine toe shape.

Here you can see the boot shaft’s unusual high front and high back with the U-shaped sides.Third, the information about material and construction is elaborated on in the Description field, in sentence form. The cataloguer needs to know quite a bit about the elements of the footwear. Characteristics such as style, colour, toe shape, heel type and height, embellishments, and sole are noted. For this pair of boots, I will start by mentioning that these are carriage boots, which means they were worn for carriage or early automobile rides, and that the upper is cut in the Juliet slipper style, which is the traditional name for the high front and high back with U-shaped sides. I will describe the silk and metallic-thread brocade and note how it has been cut to fit perfectly symmetrically on the seams at the top of the foot and at the heels (called the ‘quarters’). The two seams will be mentioned: centre back and centre front seams only, indicating a high quality product that is constructed with the effect of the brocade’s patterning in mind. I’ll also mention that the boot shaft is 5” (12.5cm) high, that the toe shape is ‘almond’, the ‘knock-on’ style heel is ‘waisted’ (it narrows at the mid-point and flares out again before it hits the floor), and that the decorative feather trim edges the complete perimeter of the ‘topine’ (the top, curving edge of these boots’ uppers).

Note the waisted heel shape on the boots. The knock-on heel construction is clearly seen in the second photo.Here you can see the finely stitched seam down the centre front of the boot. The matching of the brocade’s pattern on the left and right pieces are exact at the toe, showing the careful manufacturing of these boots.

My next blog post will continue cataloguing these boots. Stay tuned.

Suzanne Petersen, Collections Manager

0 comments