Technology and Design for Speed and Agility

We are celebrating the official launch of our new virtual exhibition Boots & Blades: The Story of Canadian Figure Skating at bootsandblades.ca. The exhibition is in French and in English and contains information on the development of the sport from 1600 to 2022. There are over 40 rarely seen videos and more than 350 images, artefacts and audio clips. The site is fully accessible with captioning, transcripts and more.

This blog will focus on some of the research that went into two sections of bootsandblades.ca: “1920-1945 Form Follows Function” and “1945-1965: Age of Internationalism.” Previously, I’ve written about early blade technology and also the origins of maker marks applied on skates. Both of these approaches give clues to when the skate was made. As we move forward in time to the middle of the 20th century, the sport continued to develop. At this time, skaters were doing fancy figures much less, having reduced the practice of tracing figure-8s and other line shapes into the ice. There was still a figure-8 component to the sport (figures), but it accounted for about half of the skill-set required to be a champion. The other half of the assessment was the free skate component. This is where changes in the sport were dramatic! The sport was getting more athletic and there were changes to the technique of figure skating.

So, how could a skater improve their performance in the free skate category? Adapting the skates to their needs was one way. Technology of materials and improvements in design are two areas in which we see skates improve at this time.

Unworn high-end skating boots made by E. Schmacher a.s., St. Moritz, Switzerland, c. 1930 -1938. Note the rounded toe for more toe movement. A view of the bottom shows the markings for blade placement.Boot design. Boot design was improved by lowering the leg shaft to just below the skater’s calf, allowing for more free knee and ankle movement. The boot also allowed for more room in the toe area and a good fit over the instep provided improved overall support. The 1930s Schmacher boots shown here have all these features. It is interesting to note that boots and blades were still manufactured and sold by separate companies at this time for all levels of customers. High-end boots and blades have continued to be made and purchased separately, and still are to this day, but skates intended for leisure by the general public started to be sold as a ‘kit’ around this time. As the cost of skates came down, more people could buy them. Incidentally, one of the first companies to offer the kit of boots with blades was Spalding in the United States of America.

Blade design. Blades in the early 20th century were supported with only two stanchions. The toe of the blade was not connected and simply curled upwards, artfully. In the 1930s, a third point of connection became popular and it remains on blades today. This third connection is at the toe, as is illustrated by this early pair by CCM. This design improved stability at the front of the blade, making it preferred for the more athletic movements of the new skating style. The toe pick feature would be integrated on this type of blade soon after.

These CCM blades are marked with the Toronto Junction CCM factory location. Canadian, c. 1930-40s. Note that the blade is connected to the sole mount in three places.Technology. The new free skate category required skaters to have a good grip of the ice. Sharpening the blades with deeper edges improves grip and control on the ice. The other effect of deeper edges is reduction in speed. The skater has to push ever harder to move when the blade has deep edges. A balance is needed therefore: not too much edge, just enough to grip the ice and enough for the moves performed.

The edges create resistance, and in doing that they slow the speed of the skater. Shallow edges allow the skater stability, speed and smooth motions. Speed skates, for example, have shallow edges. Deeper edges allow for precise moves needed for complex footwork and jumps. The deeper blade sharpening curve is used by free skaters today, allowing the needed control for the athletics. Still, blades that are cut too deep will slow down the skater, cutting too deeply into the ice. A precise balance is needed to achieve the correct blade sharpening to the exact needs of the skater.

Getting the right boots and blades is critical to a skater’s performance. The design and technology of skates is improving and changing all of the time. Beyond skates, the other aspects that will influence a skater’s performance include the quality of the ice surface, training, coaching, practice and artistry to name a few.

Suzanne Petersen, Collections Manager

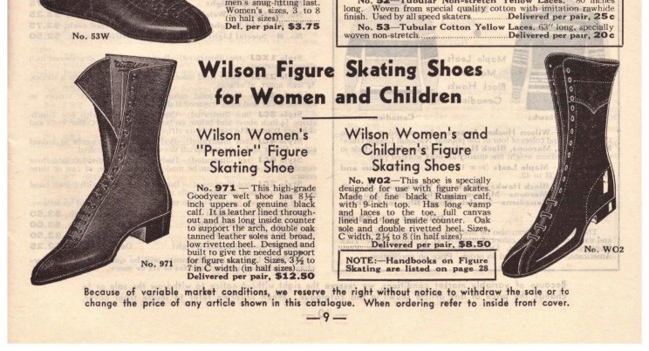

The older boot style with higher leg shaft and narrow, pointed toe influenced by street attire. Wilson Skating Shoes catalogue, 1935-1936. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac The older blade style with only two stanchions. C.C.M. advertisement in the Toronto Skating Club Carnival Program, 1932. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac Wearing the older styles of boot and blades, French champions Andrée Joly and Pierre Brunet perform in the late 1920s. Courtesy Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame]

0 comments